I grew up in Berlin, between lakes and the forest, in what I was told to be “such a green city.” After moving to Singapore for college, however, I had to confront the truth – Berlin was far behind in building a green city, failing to reconnect people and agriculture with political support and interest.

After passing most of my UA journey so far here in Singapore, I now wanted to look back home. I was surprised, that different from the Singapore’s “30 by 30” goal (Singapore Food Agency), Berlin’s 2030 “green” city plans, the “Berlin Strategy,” do not include a word about urban food production (Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment, 2013).

I will outline my findings of how UA in Berlin started as a tool for mobilisation, to show how for Berlin’s urban farmers, UA is a form of emancipation or business rather than a celebrated government narrative. This will allow formulating the prediction and recommendation about the future of UA in Berlin, that it will only become a substantial food-supplying sector if government and policymakers incorporate UA into their planning and collaborate with all stakeholders involved.

Berlin’s UA and Emancipation

After the countercultural naturalist hippie movement had passed Berlin in 1980, conservationists, ecologists, and activists continued to fight for ecological protection in the city (Lachmund, 2013). They build the founding movements that oppose heavy construction on sites that can be re-greened or reclaimed for the community until today.

The case study of the “Prinzessinnengarten” or “princes garden,” whose protection from privatisation and transformation in 2009 is shown below, is since an outstanding example of the multifunctional and inclusive nature of urban agriculture, with more than 1000 volunteers and 70000 visitors annually (Clausen, 2015). Yet, although offering a semi-public space for a diversity of social, cultural, educational, and political functions, the founders have to constantly fight for its continuity and in 2012 and already collected over 30000 signatures for their cause (Clausen, 2015).

German city gardening has also made proud history through its “Schrebergärten,” a system of locally managed individual garden allotments that has existed for over 150 years (Thornton, 2018). According to Thornton, although only ~10% remain, they are some of the only legislatively controlled urban farming spaces today, as the managing association requires their members to grow fruits and vegetables.

As inspiring as Clausen’s Prinzessinnengarten is today, being one of the city’s biggest community-led urban farming projects, it is in constant attack and only supplies a small part of the farmer’s diet. Furthermore, with the dying “Schrebergärten” system, systemically supported and widely accessible UA in Berlin is shrinking. For UA to become more important in Berlin’s food production, the movement needs to extend beyond small communities, activists, and individual businesses, become a part of the city’s planning.

Berlin’s Individualistic UA

The UA movement has since not just fuelled the city’s artsy DIY image, but many Berlin businesses have also discovered its economic profitability.

Berlin’s modern ecologically motivated lifestyle connects urban gardening spaces with the individual interim users, space pioneers, and lately a growing number of companies (Thierfelder and Kabisch, 2016). How collaboration could come with many benefits for Berlin’s progressive DIY activists and political stakeholders involved is illustrated very nicely below (Hector and Botero, 2021).

However, with the “Berlin Strategy’s” ignorance of the city’s growing demand and possibilities for UA, real estate funds support the replacement of public community-centred urban gardens, and more individual and exclusive businesses capitalize on the growing sector (Clausen, 2015).

The Berlin start-up InFarm (infarm.com) is just one example that has especially grown in the pandemic, raised over 140€ million, and expanded to over 30 cities worldwide, to provide eco-friendly urban farm produce (Tucker, 2020).

On the one hand, such successful businesses are now collaborating with discounters and stores like METRO on their own accord, making UA produce more accessible to the public (Cointet et al., 2019). On the other hand, for UA to truly supply a significant amount of the city’s fresh produce, and for it to be widely accessible, collaboration with political actors and policymakers will be indispensable.

Is Berlin ready for more UA?

If Berlin’s consumer demand for local and organic food products and rising UA media content underline the city’s potential for ZFarming and Hydroponics, why does political planning not involve UA (Specht et al., 2016)?

Even systemically supported platforms that aim to connect free city spaces with community ideas and projects, like Coopolis (coopolis.de), do not have any records of projects involving urban agriculture.

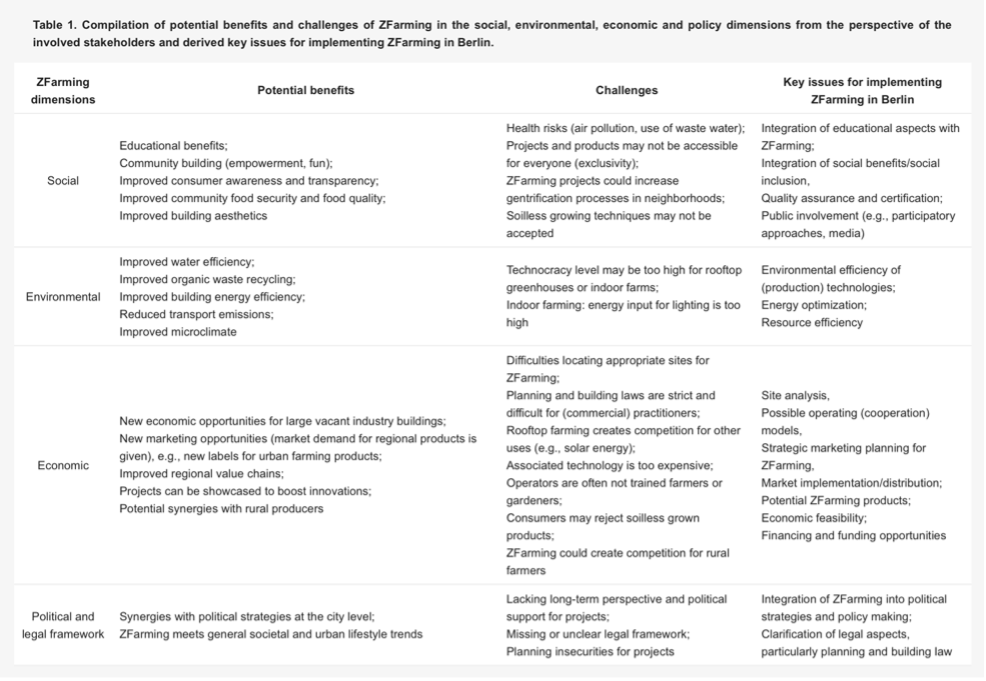

Specht argues that political acceptance will remain low as long as UA is not perceived as a mainstream planning program by their planners. We can see this trend changing here in Singapore, but also in Canada and the US. What buffers this change in Berlin are some perceived risks are associated with for example the “unnatural” production of food and the increased industrialisation of agriculture, but also health risks due to urban pollutants (Specht et al. 2016). This adherence to traditional images of agriculture businesses can be seen in the survey below done by Kathrin Specht and her team in 2016, underlining the complexity of Berlin’s UA future, but also the need for political involvement to shape imaginaries.

For UA to become important in Berlin’s food provision, its perception by political actors needs to shift. It is time for planners and policymakers to see the potential in collaboration with civic actors for better space management and in the incorporation of UA in Berlin’s city strategy (Thornton, 2018).

The Need for Collaboration

As much potential as UA has in Berlin, there are many hurdles on the path to such political acceptance and collaboration with social movements, businesses, and the stakeholder shown involved (Specht et al., 2015).

One of the biggest impediments to negotiation is Berlin’s lack of an agriculture ministry. Thornton highlights, how this leaves 3 million consumers without representation, without a voice. Many non-profits are now pushing for small state involvement, often backed by over 18 000 protestors, to demonstrate against the bureaucracy and land privatisation that limit UA and food policy introduction in Berlin (Thornton, 2018). The popular progressive image of Berlin’s community engagement stands on those activists in ‘nutrition councils,’ fighting for the necessary political commitment to collaboration (Thornton, 2018).

A second obstacle, which according to Clausen is limiting a food policy and UA in Berlin, is the Free Trade Agreement (Thornton, 2018). He explains how where decisions are made on an EU level rather than locally, it is inexorably fuelling industrialisation and limiting new systems like UA. This means, that despite a growing 10% of the German market share in locally grown organic food, big traditional discounter chains like ALDI and Lidl will continue to be prioritised (Thornton, 2018). He points at how this drives activists and policymakers apart, leaving the former in favour of rural small-scale farming and protests like the “Grüne Woche” demonstrations, rather than the collaboration with bigger players (Thornton, 2018).

So, if an informal process for city–community engagement in urban food systems is not progressing, the interest in UA and collaboration needs to begin on the city’s government level. There is hope, as more planners are vouching for UA in political spaces, and small wins like the reclaimed Friedrichshain neighbourhood garden show their increasing leverage (Rosol, 2010). UA’s immense potential in for example food security, the subsidy of low-income families’ nutrition, but also environmental conservation, is only in reach if politicians choose the collaboration of all stakeholders (Specht et al. 2015).

The Future of Berlin’s UA

If UA will be considered in future “Strategies,” or in response to the climate policy revisions happening these days in Germany, the question will be how to involve all stakeholders and prevent places, movements, and narratives from being appropriated in the process. Another challenge Clausen formulates is to find middle ways, which include individuals and businesses while preventing the transformation of “commons into commodities, alternatives into lifestyles, and poor neighbourhoods into gentrified areas.”

Beneficial collaboration would for example preserve and improve the soon unprotected Schrebergärten network in the effort to understand ecological and social issues (Thornton, 2018). Moreover, Lachmund showed that the place of nature in the modern city, and its political use, are changing, and he reminds us that in the formation of urban policies, politics and nature remain inseparable.

The enormous potential of UA in Berlin is as diverse as its challenges, while both are much more complex as shown in this research and the summary below (Specht et al. 2015).

To Thornton, it is Berlin’s community engagement, which makes its case hardly replicable, yet it is also this engagement, which shapes the city and will ultimately fight for more sustainable and accessible UA. In studying the UA movement, it is most crucial to understand such localities, urban geographies, and motivations to better frame discussions of the possibilities for city–community partnerships, sustainable cities, and urban agriculture (Thornton, 2018).

“Tomorrow’s possibilities grow in the gaps of conventional planning processes, nurtured by social desires and needs.”

– Marco Clausen, 2015

Sources:

Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment. 2013. „Berlin Strategie.“ Metropolis.org. Accessed at: https://use.metropolis.org/system/images/1935/original/BerlinStrategie_Broschuere_en.pdf

Clausen, Marco. 2015. “Urban Agriculture between Pioneer Use and Urban Land Grabbing: The Case of “Prinzessinnengarten” Berlin.” Cities and the Environment 8: 1-5. Accessed at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1190&context=cate

Cointet, Florian, Marie Garnier, and Flavien Sollet. 2019. “Promoting access to produce sourced from urban agriculture: the case of Metro and Infarm.” Field Actions Science Reports 20: 116-119. Accessed at: https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5886

Hector, Philip, and Andrea Botero, 2021. “Generative repair: everyday infrastructuring between DIY citizen initiatives and institutional arrangements.” CoDesign: 1-17. Accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1912778

Lachmund, Jens. 2013. “Greening Berlin: The Co-Production of Science, Politics, and Urban Nature.” The MIT Press. Accessed at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vjrr7

Specht, Kathrin, Rosemarie Siebert, and Susanne Thomaier et al. 2015. “Zero-Acreage Farming in the City of Berlin: An Aggregated Stakeholder Perspective on Potential Benefits and Challenges.” Sustainability 7: 4511-4523. Accessed at: https://doi.org/10.3390/su7044511

Specht, Kathrin, Rosemarie Siebert, and Susanne Thomaier. 2016. “Perception and acceptance of agricultural production in and on urban buildings (ZFarming): a qualitative study from Berlin, Germany.” Agric Hum Values 33: 753–769. Accessed at: https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1007/s10460-015-9658-z

Specht, Kathrin, Thomas Weith, and Kristin Swoboda et al. 2016. „Socially acceptable urban agriculture businesses.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 36: 17. Accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0355-0

Thierfelder, Holle and Nadja Kabisch. 2016. “Viewpoint Berlin: Strategic urban development in Berlin – Challenges for future urban green space development.” Environmental Science & Policy 62: 120-122. Accessed at: https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.09.004

Thornton, Alec. 2018. “Space and Food in the City: Cultivating Social Justice and Urban Governance through Urban Agriculture.” Palgrave. Accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89324-2

Tucker, Charlotte. 2020. “Berlin-based Infarm raises €144 million during pandemic to grow largest urban vertical farming network in the world.” EU-startups.com. Accessed at: https://www.eu-startups.com/2020/09/berlin-based-infarm-raises-e144-million-during-pandemic-to-grow-largest-urban-vertical-farming-network-in-the-world/

Rosol, Marit. 2010. “Public Participation in Post‐Fordist Urban Green Space Governance: The Case of Community Gardens in Berlin.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34: 548-563. Accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00968.x

Singapore Food Agency. “Food Farming.” Accessed at: https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-farming